How to Ask for Help

And the real reason we hesitate

Welcome to all the new members of the Practically Deliberate community!

It’s been a whirlwind behind the scenes…among other things, the paperback version of my book launched last month! I appreciate your patience while I’ve been uncharacteristically quiet here (to see other places I popped up, scroll to the end).

Thanks to all who picked up a copy; helped spread the word; or wrote an Amazon review (you can still do that here; they really do matter!).

This time of year can feel especially hectic — particularly for those who live or work with young people.

I hope today’s post (a 10 minute read), all about asking for help, is timely.

You’ll learn:

Why it’s hard for so many of us (myself included) to ask for help;

Why we should push through our discomfort and do it anyway;

Practical ways to ask for help if you, too, find it challenging.

Ready? Read on!

The Backstory

When Money and Love was first published, my co-author and I hired a well-known PR firm to help get the word out by pitching us to various publications.

It wasn’t inexpensive, so we decided against hiring additional PR support for the paperback. Instead, I’d leverage my learnings and relationships to promote it.

This required me to ask a lot of people for help — which I found hard.

I’m game to lend assistance when others ask, but it turns out that to this eldest daughter, asking for help doesn’t come naturally.

When I mentioned this on LinkedIn, several others commented that asking for help was hard for them, too.

Then, on a call with two colleagues, one shared she was going through a tough time personally and professionally.

I asked her a question I sometimes ask my kids: “Do you want to be helped, heard, or hugged?”1

“Heard,” she replied. We listened while she elaborated…but couldn’t resist weighing in.

Afterwards, we apologized via text for jumping into ‘help’ mode even though she asked to be heard.

She responded “Oh, I’m glad you helped! The only reason I didn’t ask for it is because I wasn’t sure exactly what I would be asking for.”

My friend is a brilliant, capable person. Those who commented on my LinkedIn post are equally brilliant and capable. So why do we all find it so damn hard to ask for help!?

I had to dig into it…

Why it’s so hard to ask for help

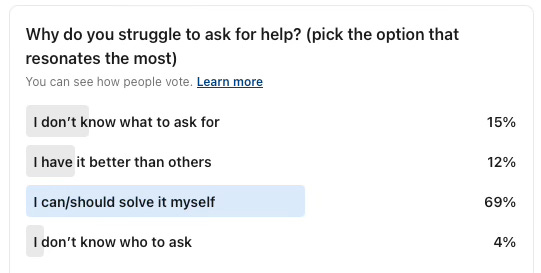

I posted this question on LinkedIn. Overwhelmingly, people said what holds them back is feeling like they can/should solve [an issue] themselves.

A few elaborated: they know everyone is “super busy” and don’t want to “bother” or “impose on” others. Or they suspect it will take just as much effort to ask for/obtain help as it would to do it themselves.

But what if the real reason we don’t ask is that we’re actually afraid of rejection?

I spoke with Ania Jaroszewicz, a professor at UC San Diego’s business school whose research focuses on the psychology of asking and rejection, among other things.

She shared that aside from lack of awareness (“I don’t know what to ask for” or “who to ask”), there are real psychological costs that prevent people from asking for help.

These costs include feeling shame about needing help; reluctance to feel indebted to others; and wariness about the potential for rejection.

She noted hearing “no” isn’t the only thing that feels like a rejection — getting a less-than-enthusiastic yes can also feel discouraging.

In a co-authored paper, she points out that even if we think someone is very likely to help us, our human tendency to over-weight the negative may cause us not to ask, because “being rejected hurts more than being consented to feels good.”2

Perhaps instead of putting ourselves out there and risking rejection, we give ourselves reasons not to ask in the first place.

Why we should push through our discomfort

There’s substantial evidence in favor of acknowledging the potential for rejection…and then asking anyway.

Asking makes others feel good

When people ask me for help, it makes me feel good. But when I think of asking others for help, I worry I’ll inconvenience them.

It turns out I’m not unique in this regard.

A study of more than 2,000 adults showed they “consistently underestimated others’ willingness to help, underestimated how positively helpers would feel, and overestimated how inconvenienced helpers would feel.”3

Asking makes you more likeable

If making others feel good is not reason enough for you to ask for help, keep the “Ben Franklin effect” in mind.

This phenomenon, referenced by Ben Franklin in his autobiography, describes how asking people for help actually causes them to like us more (this was later borne out in psychological research).

Why? If someone does you a favor, they’re more likely to rationalize it by telling themselves they like you (after all, why else would they go out of their way to help you?).

Asking gets easier the more you do it

In a recent newsletter, Oliver Burkeman noted it’s important for many of us to get better at disappointing people (aka protecting our boundaries).

The best way to do that, according to Burkeman? Practice. He exhorted readers to “set the intention to disappoint at least one person, in some real way, over the next 24 hours.”

Once you do, you realize the world won’t end (and they won’t hate you forever), which emboldens you to do it more often.

The same logic applies to asking for help. Go ahead — set the intention to ask at least one person for help, in some real way, over the next 24 hours…and see what happens (let’s just hope the person you ask for help isn’t trying to get better at disappointing people!).

When I asked people for help getting the word out about my paperback, I was delighted by how many said yes enthusiastically, which encouraged me to make more, even bolder asks.

Practical ways to ask for help

If you also struggle to ask for help, here are a few ways to build your asking muscle.

Practice with small things

Jaroszewicz’s research shows that fear of getting rejected deters us from asking for help. Paradoxically, this can lead to people being less likely to ask for help the more they need it (because getting rejected hurts even more in that situation).

If you’re not already a practiced asker, start with a relatively minor request. Is there a small problem someone could easily help you solve at a low cost to them?

I had one recently. My husband (who covers all things food-related) was on a work trip. I successfully packed lunches for everyone in the morning (yay!) only to discover that I’d accidentally switched lunch boxes with my older son (groan).

Of course, it was the day he goes straight from school to rock climbing, arriving home ravenous even on days he’s eaten a full lunch.

Knowing my son was unlikely to eat my salmon, I texted the family we carpool with, explaining the situation and asking if they could bring my son a protein bar.

They said of course, solving the problem and letting me carry on with my day without visions of him fainting from hunger and falling from the climbing wall.

Ask for perspective

When my colleague said she didn’t ask for help because she wasn’t sure exactly what to ask for, we offered perspective.

She was feeling overwhelmed, so we suggested things she might subtract (research shows we’re less likely to consider solutions that involve subtracting vs. adding).

We also suggested what she should prioritize (sometimes it’s hard to do this for someone else, but in this case, it was clear).

If you’re feeling overwhelmed and wondering how to tackle everything on your plate, consider asking your manager or a wise friend to provide perspective.

It’s challenging for us to have perspective about our own situation because we’re in it. By definition, it’s much easier for someone else to offer perspective (you can always decide whether to take or leave their advice).

Normalize the expectation of helping within a group.

When a norm of helping is made explicit in a group, it becomes easier to ask for and receive help.

Adam Grant has written about the power of a reciprocity ring, a structured exercise where people make meaningful requests to a group with the expectation of offering assistance to others’ requests.

I’ve experienced the power of a formal reciprocity ring directly (Professor Frank Flynn ran one in my first OB class at Stanford GSB). But I’ve also had the good fortune to be part of other communities where helping is a norm.

For example, I’m in a group of authors (primarily academics) who meet monthly over Zoom to share ideas, advice, and introductions. A culture — and expectation — of helping runs strong within this group. For example, I first learned about Ania Jaroszewicz’s research from someone in the group who then connected us by email.

I found it easier to ask members of this group to help spread the word about my paperback because of the well-established norm of helping (thank you, Team O, for being so awesome!).

Is there a group you’re part of that has an established expectation of helping? If so, that’s a great place to start building your asking muscle.

A word on professional help

Sometimes we need more help (or a different type of help) than a friend or acquaintance can provide.

I’m a big believer in the help third party experts — including therapists, career coaches, and financial advisors — can offer.

At different points in my life, I’ve hired professionals (including all those mentioned above) with specialized expertise to help me when I needed it.

This can be pricey, and to be clear, I realize it’s a significant privilege to have the funds to spend on this type of help. However, a useful reframe for me has been to view it as an investment (vs. a pure expense).

It can be daunting to find trusted experts, and I’ve typically relied on my network for referrals. I also make it a point to share names of my trusted experts with others (except my beloved tailor, as explained in my deliberate closet post!).

In that spirit, I wanted to share an expert with you. I recently revamped my personal website, and I’m thrilled with the result. My partner in this effort was Barbara Byrne of Wise Wolf Creative (she also helped build our book website). Barbara was a collaborative, responsive, and patient partner in bringing my vision to life. Don’t hesitate to reach out to her if you have web-related needs!

Abby’s Latest

While I enjoyed sharing behind-the-scenes activities leading up to my paperback launch, I’m delighted to return to the original purpose of this section: to recommend my latest obsessions (as always, I’ll disclose affiliate links, and there are none here)!

Today I’m singing the praises of my W&P silicone personal popcorn popper. Freshly popped popcorn is one of my favorite snacks. In fact, I will eat as much fresh popcorn as is in front of me. Traditional stovetop methods make a lot of popcorn, and microwave popcorn isn’t great for you (or the planet).

Enter this magical personal popcorn popper, which makes the perfect amount of popcorn, is easy to clean, and collapses to 2” to store.

Pro tips: to make cleanup easier, don't use any oil in the bowl. Instead, once it’s popped, transfer it to another bowl for eating (be careful, the silicone can get a bit hot), and spritz with cooking spray before sprinkling popcorn salt on it.

Deliberately yours,

Abby

P.S. Thanks to all who said yes to my request and mentioned my book in their terrific newsletters. Check out Shira Gill’s post here, Alison Fragale’s here, Laura Fenton’s here, Yael Schonbrun’s here, Lindsey Stanberry’s here, Todd Kashdan’s here, Colin M. Fisher’s here, Rashi’s here and Charles Moore’s here. Phew…that doesn’t include the wonderful podcast hosts I joined. I guess I did a decent job asking for help after all!

Bénabou, R., Jaroszewicz, A., & Loewenstein, G. (2025). It hurts to ask. European Economic Review, 171, 104911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2024.104911 (quote from here: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/it-hurts-ask)

Zhao, X., & Epley, N. (2022). Surprisingly Happy to Have Helped: Underestimating Prosociality Creates a Misplaced Barrier to Asking for Help. Psychological Science, 33(10), 1708-1731. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221097615 (Original work published 2022)

Nothing fills me with a sense of purpose more than helping a friend in a bind. I admit that I do it as much for myself as for them!

Always the best thing in my inbox!